Contact

About Us

Articles

Home

Contact

About Us

Articles

Home

Understanding essential versus discretionary spending – or “needs” versus “wants” – forms the basis for sound financial decision-making. Without that, it becomes hard to control impulse spending and even harder to save successfully for retirement.

Yet, the concept is not part of financial literacy training at home or in schools. Here we see how the concept evolves over your lifetime to help ensure a happy retirement.

The challenge of deciphering needs and wants has followed you throughout your life.

At birth, you functioned from a place of survival, with needs that your parents met. But by your Terrible Twos, you discovered wants. You learned you had choices, and the world was filled with endless temptation. Everything felt like – and was demanded as – a need.

Unless you came from extreme wealth, sometime between then and young adulthood, your parents introduced you to the difference between need and want. They typically gave you what you needed, but not necessarily what you wanted. But all too often – maybe because of the taboos around the topic of money – they may not have shared the most fundamental lesson of financial literacy: balancing a budget.

It wasn’t until you were living on your own that you discovered the consequences of not balancing the inflow of funds with the outflow. For the first time, being out of balance had a real-life implication: either credit card debt or the inability to close out the month.

You may have muddled through this balancing act until you got your months to close. But very rarely did the message get broken down to the simple concept of needs and wants, which would have made the idea of budgeting much easier to understand and adopt.

Intuitively, using a hit-or-miss approach, you finally got it. Others, whether out of not knowing or the inability to resist peer pressure to keep up with others, may have continued to struggle, never differentiating between needs and wants and never getting control over their finances.

In the world of personal finance, those terms – needs and wants – are called essential spending and discretionary spending. They are fundamental to the budgeting process and to making responsible spending decisions. Without clarity around those concepts, saving successfully for retirement becomes extremely challenging.

Essential spending – what was referred to as a “need” – is mandatory spending that you have no choice over. You need to have these things, and you need to pay for them. This spending includes:

Essential spending can be fixed or variable. It is fixed if you pay the same amount each time, such as your monthly rent or annual insurance premium. It is predictable. It is variable if it fluctuates, as your electric bill will depending on how much power you use. Groceries, gas expenses and clothing vary, too.

Discretionary spending reflects your “wants.” They are more lifestyle-driven and include all the things you choose because they bring you some satisfaction. This spending can include:

Some discretionary expenditures may feel like needs, but absolute control over your money will come when you acknowledge that you choose each of those activities. You can choose to go with or without.

Once there is an awareness of the importance of managing your money – whether to save for retirement or to live a less stressful life – you find yourself shifting from spontaneous spending to managed spending. And managed spending requires a budget or spending plan.

In a budget, the elements of wants and needs come back into play as you define the allocation of your disposable income. Here an example may be helpful.

Senator Elizabeth Warren wrote about one of the better-known spending plans in her book called "All Your Worth: The Ultimate Lifetime Money Plan." In it, she and her daughter described the 50/30/20 Rule of Thumb. Its purpose is to help working-class families plan their spending to prepare for the future and any unexpected situations. Of one’s disposable income, the guideline recommends allocating:

The goal is to track each month’s spending, categorize expenditures and see how close or far you are from the 50/30/20 allocation. It may take several months of adjusting your spending, with the understanding that the best formula for you may be a variation of 50/30/20. In any case, using the rule increases your awareness of financial habits and puts a spotlight on the importance of saving and paying down debt.

Your needs and wants may shift at three different times in your life:

But along the way, each decade seems to present new challenges to the accumulation phase.

In your 20s, you begin earning an income, and you use your newfound freedom to explore who you are and what is important to you. Unfortunately, the chance of retirement savings making it on the list of priorities is relatively low. It seems too far off in the future to be relevant.

This is where a significant opportunity is lost. Few young adults understand how the element of time can ease the process of saving for retirement. Even starting with seemingly unimportant amounts – saved every week or month – can provide an invaluable head start.

The tool is compound interest. By investing your money and continuously reinvesting your earnings, small amounts can grow impressively. For example, using a 6% return on the investments and calculating annually, a 25-year-old who starts investing $200 per month will have a nest egg of over $370,000 by age 65. But by waiting to start at age 35 instead – with everything else the same – at age 65, the nest egg will be worth slightly less than $190,000.

In your 30s, you are married with children – or thinking of children. Your needs escalate as you buy houses, cars and insurance. And the damage done if you mismanage your income, needs and wants now extends beyond yourself to your spouses and children. With all that pressure, the thought of retirement stays buried.

By your 40s, you are headed toward your peak earning years. While this could be an easy time to start setting money aside for retirement, there’s a good chance your lifestyle has grown as fast or faster than your income: a bigger house, a second car, vacations for the family and costly health care for all. Saving for college may join the needs list but not retirement.

It is in your 50s when retirement tends to come front and center. Suddenly that deadline that seemed so far off looms large. If you have developed a retirement plan with a financial professional, this is when you start trying to play catchup. Your needs and wants get a thorough examination. You may freeze (or reduce) the cost of your needs and pare back materially on your wants. You now have a goal that is imminent enough to change your behavior.

But your 60s are when you approach the “retirement finish line” and when you have the most focus on your spending, whether on wants or needs. Sacrificing feels easier because it’s not for that long, and you have to maximize the accumulation phase of your retirement plan. You start envisioning yourself in retirement.

The life expectancy of those who reach adulthood has not changed much in recent decades. What has changed at retirement age is the state of health, energy levels and expectations of what retirement will look like. And you know you will need to finance 20 to 30 years after retiring at age 65.

One expectation is that, once you retire, your cost of living will go down. Many of your needs will no longer be required. You won’t be working, commuting, dressing for work, eating away from home and many other work-related expenses. Because you will be on Medicare, your medical costs are expected to go down. And you expect your housing costs to go down, too.

But what actually happens?

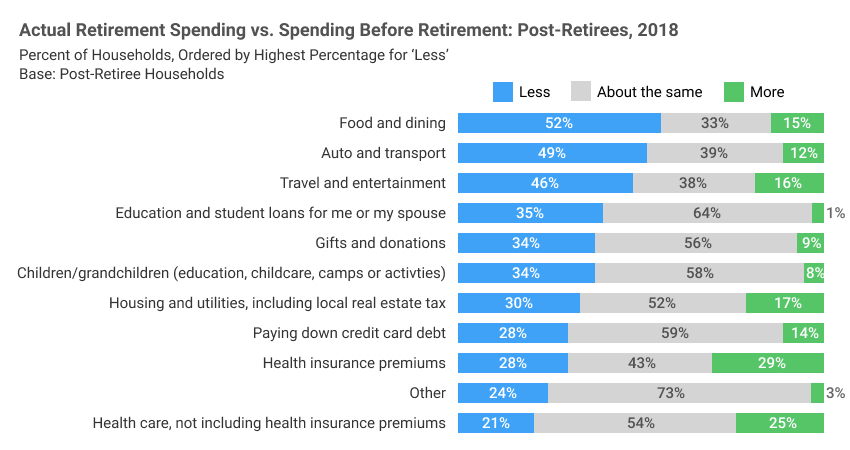

Forbes reports on a study carried out by the financial market research firm Hearts & Wallets. It asked workers between the ages of 53 and 64 if they thought they would spend less, the same as or more on certain expenditures once they retired. The firm also surveyed retirees about the same expenditures, asking if they are spending less, the same as or more than their pre-retirement costs.

According to the results, pre-retirees are not particularly effective in projecting costs. While retirees spend less on many of the discretionary expenses, two essential areas showed material discrepancies.

Forty-six percent of working pre-retirees expected to spend less on housing, but that is only the case for 30% of retirees, and 17% are facing higher expenditures. Health care costs and health insurance premiums are two categories where a significant percentage of retirees find themselves spending more than during pre-retirement: 25% of retirees on health care and 29% on health insurance premiums.

Following is the table of the Hearts & Wallets findings:

In pre-retirement, if financial circumstances (either personal or market-driven) create the need to give up spending in a discretionary category, you have two options. You can work more or find extra income to continue affording the expense. Or you can forgo the expense in the interest of maintaining stability in the rest of your finances. There is no major psychological damage done.

And if you discover that your savings status indicates you may have to give up something important in retirement, you can work longer before retiring to increase your savings as needed.

You have actions you can take to correct or change the situation.

But once in retirement, the psychology of maintaining a pre-determined lifestyle may make giving something up more difficult. The difference between essential and discretionary may be less cut-and-dry and more of a continuum. So, while you are still in the accumulation phase, it may be necessary to rethink your projected retirement expenses and analyze each individually.

Some discretionary expenses may actually be essential to your well-being and fulfillment, while some essential expenses may play less of a critical role. For example, what part of housing is a deal-breaker and what part matters less? What part of travel – which is usually defined as discretionary – is actually essential? Visiting grandchildren? Spending holidays with loved ones?

Essential expenses may not be the entire categories but specific expenses within each category. Redefining projected expenses in this way will provide a clearer picture of how flexible your retirement spending is. Knowing how many of your expenses would affect you seriously if you had to give them up tells you how flexible you can be in response to an event such as another 2008. And you want that knowledge as you are developing the plan with your planner, not after you have retired.

Essential expenditures are typically covered by stable and lifetime-guaranteed income streams such as Social Security, pensions and annuity-type instruments. Discretionary expenditures are more likely covered by a diversified investment portfolio that can be subject to market risk. Communicating your true needs and wants to your planner will allow for the right combination of no-risk and at-risk income sources.

The purpose of a plan is not just to cover life’s essentials. It is to provide the aspects that are important to you, that support a chosen lifestyle and that define a successful retirement.

Yet things happen. If something like the 2008 crisis were to occur after you retire, knowing that the deal-breakers of your retirement are covered by guaranteed sources will go a long way to making the response tenable.

The pandemic has put critical income sources at risk for people in the accumulation phase of retirement planning. Job losses and the illness itself may have halted accumulation temporarily. Sacrifices such as working overtime, taking on a second job or somehow increasing the household income may be required to maintain the original retirement plan. Or retirement may have to be delayed.

For those already retired and in the spending phase, the pandemic has shut down many of the elements considered to be essential. In fact, the concept of essential has been redefined. For example, not only are you not traveling to see grandchildren, but for a year, you have likely been forced to socially distance and settle for FaceTime visits.

The pandemic also brought market volatility in its early months. But markets have since recuperated and, if left untouched, well-invested portfolios should have been helped, not hindered.

As the economy continues to open and some semblance of normalcy is reached, it may be critical to re-do the exercise of defining your specific – not category-level – essentials. Sharing that information with your financial professional will allow for an updated plan that reflects your new priorities. Depending on what has changed, rebalancing your portfolio may be required, perhaps shifting part of the at-risk portion to a carefully selected immediate annuity if essential spending has grown.

In short, the needs and wants that have followed you throughout your life have had to undergo a more refined definition to serve you in retirement. And, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be time to define them once again.

Alliance America is an insurance and financial services company. Our financial planners and retirement income certified professionals can assist you in maximizing your retirement resources and help you to achieve your future goals. We have access to an array of products and services, all focused on helping you enjoy the retirement lifestyle you want and deserve. You can request a no-cost, no-obligation consultation by calling (833) 219-6884 today.